Picture a world where doctors can adjust brain activity without surgery—using nothing but sound waves. Thanks to groundbreaking research led by Dr. Hong Chen at Washington University, this futuristic idea is inching closer to reality.

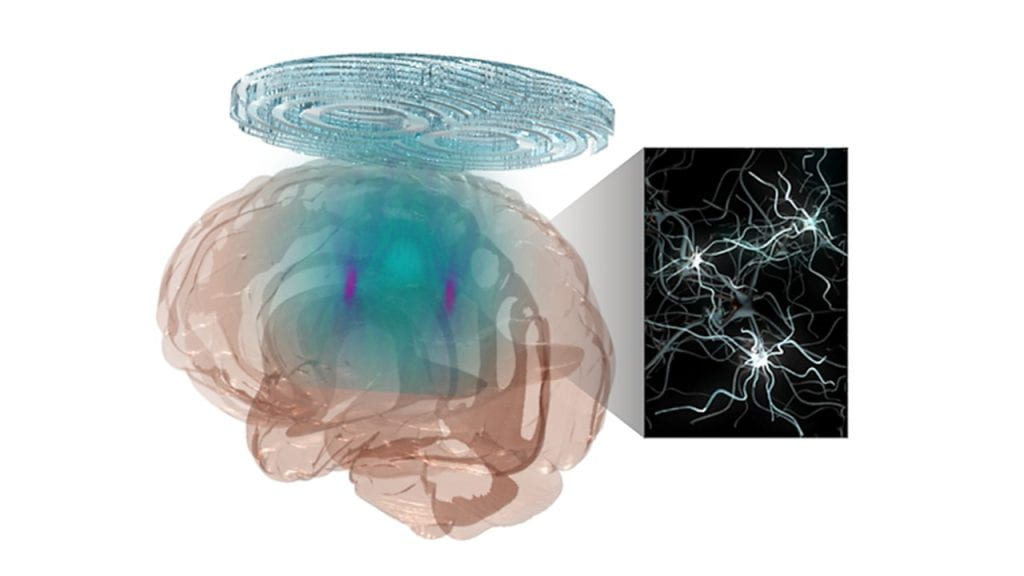

Her team’s innovation, called Airy-beam holographic sonogenetics, uses ultrasound to target specific neurons in the brain—no implants or scalpels required. Think of it as a “remote control” for brain cells, but instead of buttons, it relies on sound waves curved like a rainbow.

Musumeci Online – The Podcast. It is perfect for driving, commuting, or waiting in line!

How It Works: A “Sound Rainbow” for Precision Medicine

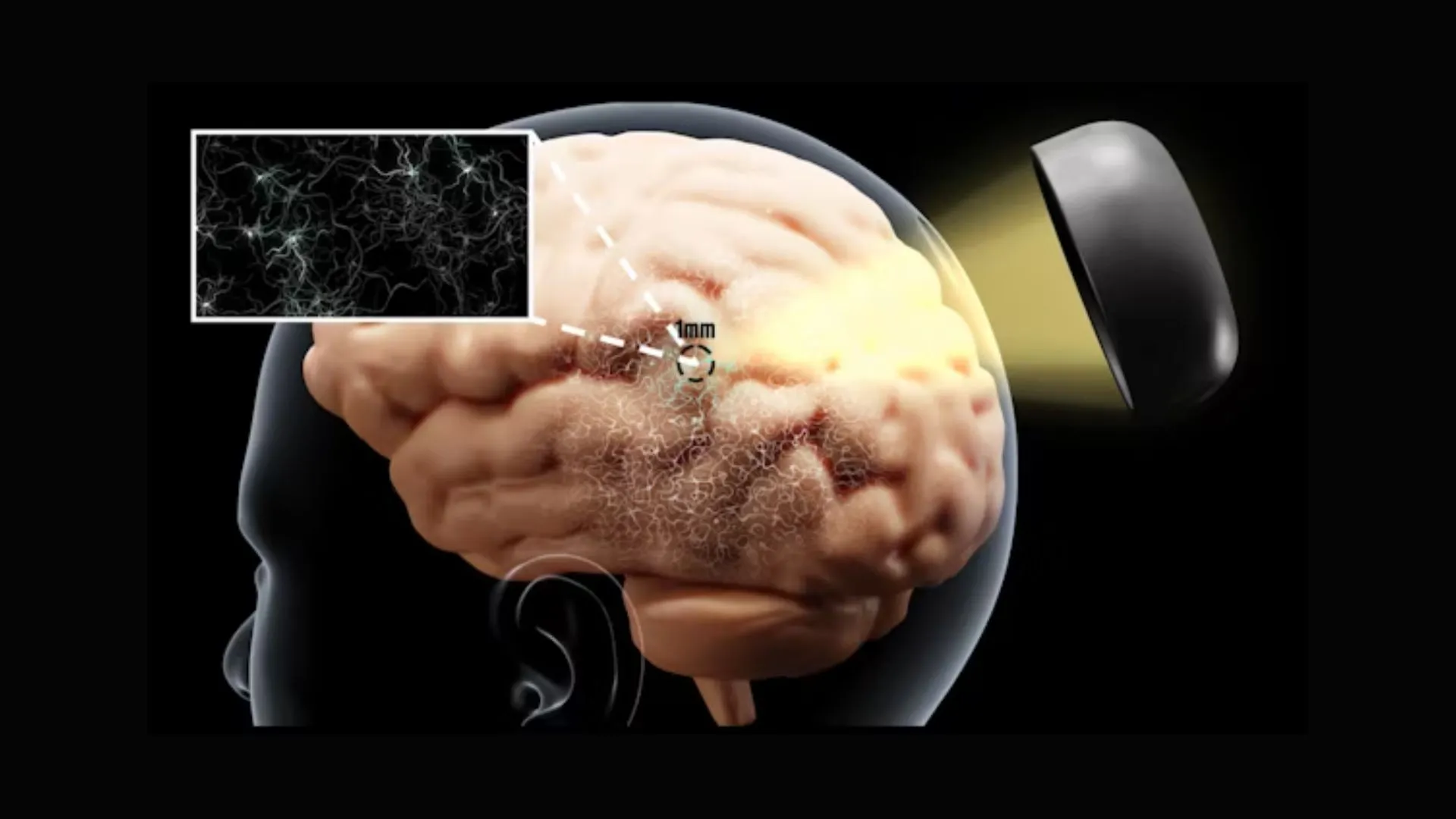

Traditional ultrasound spreads broadly, like a flashlight beam. But Dr. Chen’s method bends sound waves (using the Airy-beam effect) to create a ultra-focused point of energy—like using a magnifying glass to concentrate sunlight.

Here’s the magic:

- Virus as a Delivery Helper: A harmless virus carries genetic instructions to specific neurons, making them sensitive to ultrasound.

- Wearable Tech: A lightweight device on the head emits curved sound waves, activating only the targeted cells.

- Parkinson’s Breakthrough: In mice, this restored movement by stimulating brain areas linked to motor control.

An Airy beam is like a sound-wave rainbow,” Dr. Chen explains. “It curves and focuses energy exactly where we need it.

Why This Matters

- Non-Invasive Alternative: Unlike deep-brain stimulation (which requires surgery), this could treat conditions like Parkinson’s with a wearable device.

- Beyond the Brain: Potential uses include diabetes (targeting pancreas cells) or heart rhythm disorders.

- Inspired by Galileo’s Mistake: The Airy-beam effect was first noticed in 1830s astronomy—proof that old science can spark new miracles.

Challenges Ahead

While promising, the tech isn’t ready for humans yet. Key hurdles:

- Skull Thickness: Human skulls may scatter sound waves differently than mice.

- Wearable Design: Patients might need to wear the device continuously.

But as Dr. Sreekanth Chalasani (Salk Institute) notes: “If it means avoiding brain surgery, people may gladly embrace it.”

The Bigger Picture

Dr. Chen’s journey—from a curious student in China to pioneering ultrasound genetics—shows how blending fields (physics, genetics, and neurology) can redefine medicine.

“I never imagined sound could manipulate genes,” she reflects. “Now, it’s opening doors we didn’t know existed.”

Leave a Reply